Doom Loops, Debt Spirals and Dumb Taxes

A series about the UK's worst taxes

Both the IMF and Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates hedge fund, agree that the UK is in trouble. The government is spending more than it raises in taxes, and its efforts to change this are actually lowering tax collections, not increasing them.

A doom loop occurs when government policy reduces economic activity by over-taxing it, over-regulating it, or allowing unconnected third parties to stifle it with litigation. This lowers tax revenue, which in turn causes a debt spiral if the government can’t or won’t cut spending, leading to increased debt and higher debt costs. In the 2024/25 financial year, UK public sector net debt was £2.8 trillion, equivalent to 95.2% of GDP. Public sector net borrowing was £151.9 billion in 2024/25, £20.7 billion higher than the previous year and equal to 5.3% of GDP, up from 4.8% of GDP in 2023/24.

In the 2025-6 fiscal year, the government is projected to spend £111.2 billion on debt interest, which is 8.3% of total public spending and more than double the amount spent on debt interest in 2020-21, and UK public sector net debt is projected to be £2.897 trillion. This looks likely as borrowing to fund day-to-day public sector activities was £16.3 billion in June 2025; this was £7.1 billion more than in June 2024 and the third-highest June current budget deficit since monthly records began in 1997, after those of 2020 and 2022.

Several commentators and government officials are calling for higher taxes, but unfortunately, many of the UK’s taxes are dumb taxes, which discourage the economic activity required to collect the tax. Sometimes this is the objective, but the change in behaviour is not always the one intended by the tax, as I shall discuss.

What the UK needs is smart taxes that encourage economic activity, which will produce more employment and investment, which will in turn produce more tax revenue to pay for necessary government services. However, the UK will not get out of this doom loop by tax cuts alone, and cuts in government spending are needed, but those will be discussed in another essay.

Tobacco duties and the Laffer curve

The Laffer curve describes the change in tax collected as the tax rate changes. The Laffer curve is a normal ‘bell’ distribution – where the maximum tax collection is reached at a certain tax rate and any increase in the rate beyond this point collects less tax revenue rather than more.

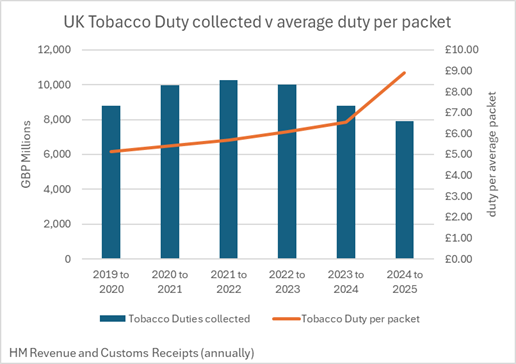

One of the best examples of the Laffer curve I have seen with real data is the UK’s tax revenues from tobacco duties, the tax maximisation point was an average duty per packet of cigarettes of £5.70 in 2021-22. Since then, tobacco duty has increased per packet, but the money collected from tobacco duties has fallen along with legal cigarette sales.

Former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak may be rejoicing at this information (his main legislative legacy was to stop anyone born after 2008 from buying cigarettes), but he shouldn’t. People haven’t stopped smoking – they have merely stopped buying cigarettes legally. See Figure 1, below.

According to the Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association’s 2024 Anti-illicit Trade Survey of 12,000 smokers, 83% of UK smokers admit to having bought untaxed (illegal) cigarettes. For London, that percentage jumps to 92% of smokers admit to having bought untaxed (illegal) cigarettes, while for Wales, the most law-abiding area in the survey, the proportion is a mere 79%. In 2023, the Westminster Council alone seized over 1 million illegal cigarettes. The Tobacco Manufacturing Association believes the government's estimate of £52,8 billion in lost tobacco duties since 2000 due to illegal cigarette sales is an underestimate.

Figure 1. The Laffer Curve illustrated by tobacco duties

This is a fantastic example of a Dumb tax. It was meant to change people’s behaviour rather than raise revenues, but the behaviour that it appears to have changed is to turn 83% of UK smokers into tax evaders.

Doop loop 1. The ‘Windfall’ tax

But tobacco taxes are small fry when it comes to Dumb taxes. The misnamed Windfall tax on oil and gas companies is not only collecting less revenue than expected, but it is also lowering investment, employment, and even driving companies out of business, or at least out of the UK.

A windfall is an unexpected and unearned gain, but no company in the oil and gas sector ever receive unearned gains – you have to own mining leases and have invested in exploration and mining equipment to get any return from an oil or gas well. Examining the history of oil and gas prices reveals that they haven’t been stable since the 1970s. Windfalls, downfalls, and sinkholes are all part of doing business, which is why there are well-organised, highly liquid, oil and gas futures markets.

However, the Conservative government under Sunak and the Labour government under Starmer somehow convinced themselves that the spike in oil and gas prices, caused by the threats of sanctions and embargoes on Russian oil and gas production, was an unearned gain rather than a temporary panic. The sanctions on Russian oil and gas never really happened; only some of the supply chains moved. (The EU still imported 54 billion cubic metres of Russian gas in 2024 and 13 million tonnes of Russian oil.) The sanctions against Russia had a minimal impact on global oil and gas production, but they caused UK and German gas buyers to panic, causing prices on UK and EU gas markets to spike.

Before the panic buying, European gas prices were about 50% higher than US Henry Hub prices. At the height of the panic, UK and EU Natural gas prices were up to ten times higher than the US Henry Hub price. But even now, August 2025, the UK and EU natural gas prices are still over 3 times higher than the US price, and with the current UK tax regime and resistance to opening new wells, they are likely to remain at this multiple or go higher.

How to cure a price spike

In a free market, higher prices encourage an increase in supply and a decrease in demand, both of which work together to reduce the price. This is not rocket science. At least it isn’t to most people, but it appears to be to the present and previous UK governments.

Instead of encouraging increased North Sea production to counterbalance the price spike, the Sunak government introduced the Energy Profits Levy (EPL), which was in addition to a ring-fenced 30% corporation tax and 10% Supplementary Charge on ring-fenced profits. Ring-fenced profits are those that cannot be reduced by losses from other parts of the company. This 40% tax rate was meant to give the UK government a fair share of the return from the UK’s natural resources. Normal UK corporate taxes were only 19% at the time. But the Dumb tax brigade decided they wanted even more, so the EPL was born.

The EPL was 25% when it was introduced by Sunak when he was Chancellor in May 2022, making the total tax on oil and gas companies 65%. The EPL was meant to expire at the end of 2025. However, Sunak then increased the EPL to 35% in January 2023, when he was the Prime Minister, bringing the total tax to 75% and he pushed the expiry date out to the end of March 2028. From November 1st, 2024, Labour Chancellor, Rachael Reeves, increased the EPL to 38% making the total tax on oil and gas 78%, extended the expiry to the end of March 2030 and removed and reduced the tax relief for oil and gas reinvestment.

So what were the results of this Dumb tax increase?

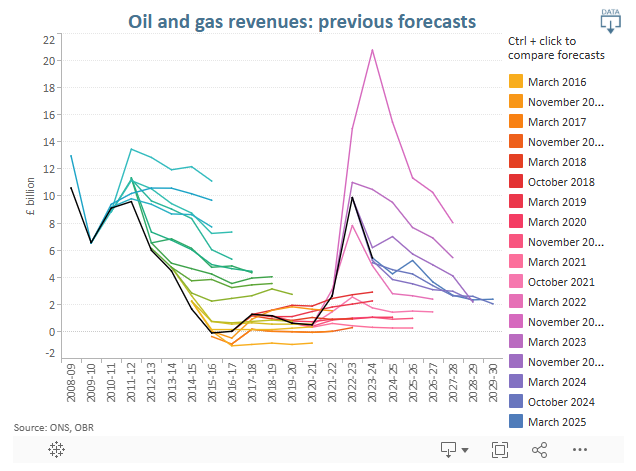

UK oil production has fallen by 40% from 52.9 million tonnes in 2019 to only 30.7 million tonnes in 2024, and gas production has fallen by 21% from 436,566 GWh in 2019 to only 343,858 GWh in 2024. And the Tax revenue? The OBR forecast in November 2022, after the EPL was introduced, that government revenues from oil and gas would be £14.9 billion in 2022-23 and £20.7 billion in 2023-24. Instead, only £9.9 billion was raised in 2022-23 and £5.4 billion in 2023-24. In March 2025, the OBR’s forecasts were much more modest; they are expecting £3.6 billion in 2026-7, £2.6 billion in 2027-8 and £2.3 billion in both 2028-9 and 2029-30.

HMRC has published the EPL figures for the financial year 2024-25; they have fallen to just £2.7 billion, a drop of £870 million from 2023-24. Did it never occur to the Treasury or our politicians that an extra 38% tax on oil and gas profits would collect less revenue?

And it is not just the loss of tax revenue.

This is a classic example of a doom loop, which will add to the UK’s debt spiral. Oil and gas companies are scaling back and cancelling investments in the UK. Some companies have announced they will quit the UK North Sea basin completely due to fiscal ‘unpredictability’. According to Offshore Energies UK, the UK is projected to lose £12 billion in tax receipts due to declining output, which will be exacerbated by capital investment falling from £14 billion to just £2 billion between 2025 and 2029. Who would have thought that a massive tax hike would have such a devastating effect on the industry?

But it is not just crude oil and gas production that is falling; oil refineries and the related manufacturing industries such as petrochemicals, plastics and fertiliser production are also closing. The Grangemouth Refinery ceased crude processing in April 2025, resulting in 400 job losses, and the Linsey Oil Refinery in Lincolnshire is in administration. Together they refined 260,000 barrels of crude per day, equal to about 22% of the UK’s total refining capacity of 1.2 million barrels. UK Consumption is about 1.35 barrels per day, so imports will have to increase by 260,000 barrels a day to make up the difference.

The Chemical operations at Grangemouth, Britain's largest chemical plant, are also at serious risk of closure. Its owner, INEOS, has warned that high energy costs and carbon taxes have made the site uncompetitive compared with its US operations.

The impact of all this on employment is enormous. It is estimated that the oil and gas mining sector loses 400 jobs every fortnight. Closure of the Grangemouth oil refinery will result in 400 direct job losses. The Lindsey Refinery will lead to 1000 job losses, encompassing employees, contractors, and suppliers. Additionally, closure of the Grangemouth Chemical operations would cause another 900 direct job losses, with thousands more jobs lost indirectly.

But it is not just jobs. SITC 5 Chemicals and SITC 3 Fuels, are the UK’s second-largest and fourth-largest goods exports. However, since 2019, using ONS Chained Volume Measures (CVM) to account for inflation, Fuel exports have fallen by 36% and Chemicals exports by 18%. Using Current Prices (CP), as all trade is actually conducted in current prices, not CVM, the only growth in this sector has been in the trade deficit. The government may talk a big game about renewable electricity, but the economy still relies heavily on oil and gas, and we need them as inputs for chemical production, plastic production, and industrial heat, as well as for transport and electricity generation.

To be fair, the UK hasn’t had a CP trade surplus in Fuels since 2003, although the most recent trade surplus in Chemicals was in 2015. But what was once a small trade deficit in Fuels has grown by 300% since 2019, while the Chemicals trade deficit has grown by 180% since 2019. Together, the UK is now paying £50 billion more for its fuel and chemical imports than it receives from its fuel and chemical exports. In 2019, the combined trade deficit was just £13.6 billion.

What a Dumb tax, who thought that was a good idea? Unfortunately, both the Conservative and the Labour governments.

Under a different tax and regulatory regime, the UK could at least be self-sufficient in fuels and chemicals, or even a net exporter. Steven Koonin, the Physicist and former US President Obama’s Under Secretary for Science in the Department of Energy, believes the UK’s Net Zero strategy is ‘Economic Suicide’ and recently urged UK policymakers to rethink their approach. If only this were our sole problem.

This is a series on UK doom loops; the second one, discussing income and employment taxes, will be out soon.