Ed Miliband has made some monumentally stupid remarks during his time as the UK’s Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero. Yes, foreign readers, that genuinely is the name of the department in the UK responsible for two completely opposing goals.

Although the UK cannot manufacture the equipment needed to harness wind and solar power for electricity, the UK believes that relying solely on these sources and achieving Net Zero would somehow grant the UK ‘energy security’. Security that depends on China continuing to sell us wind turbines and solar panels. Ed Miliband believes that, depending on China for this vital equipment, will somehow set us free from the tyranny of being dependent on foreign despots, as Miliband believes we are for oil and gas. Even though the UK’s oil and gas imports mainly come from those well-known foreign democracies – Norway, the US, and the Netherlands.

Yes, everyone except Miliband can see that the Emperor has no clothes and that his argument makes no sense. But apparently, he can play the ukulele… so he remains popular with Labour voters, though not so much with the Trade Unions these days.

This week, Miliband’s monumentally stupid pronouncement was that he intends to ‘permanently ban fracking’, claiming that fracking ‘will not take a penny off bills’ and that it will not create ‘long-term sustainable jobs’. This statement seems to suggest that without fracking, the UK has managed to lower its energy bills and generate long-term sustainable jobs. If only either were true.

There has been a moratorium on fracking in the UK since November 2019, and during that time, UK domestic electricity bills have risen by 75% from 15.9p/kWh to 26.3p/kWh, while domestic gas prices have increased by 85% from 3.4p/kWh to 6.3p/kWh. However, the much more significant issue for the UK economy is that industrial electricity prices have increased by 75% over the same period, and industrial gas prices by 120%.

So, while Miliband may have created some short-term construction jobs from installing wind turbines and solar panels, these jobs have come at the expense of jobs in other industries, such as oil and gas, oil refining, chemicals, industrial gas production, fertilisers, petrochemicals, iron and steel, aluminium, cement, ceramics, glass, etc. These were not just large employers; they were also once large export industries for the UK. The UK can’t export wind turbine construction jobs or carbon capture jobs, but it can export oil, gas, chemicals, fertilisers, etc. The ONS published a very interesting report on this problem in May 2025; it is unfortunate that Miliband has not bothered to read it.

Since 2019, the UK has lost an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 industrial jobs due to deindustrialisation and high energy prices, with the steepest declines in energy-intensive sectors such as steel, chemicals, ceramics, and paper. Manufacturing’s share of UK GDP has halved since 1990, from 16% to just 8%. Unsurprisingly, UK carbon dioxide emissions have also halved over the same period. However, this green miracle is just as false as any in the Wizard of Oz. The UK’s manufacturing sector, along with the associated employment and export revenue, has been replaced by higher unemployment and increased import costs for manufactured goods from China.

UK businesses have been hit by other costs besides energy usage; high standing charges, high wages, and high taxes are also driving companies out of business or out of the UK. Energy-intensive industries benefit from discounts on network and policy costs associated with their energy bills. However, these discounts are funded by higher charges on other sectors, such as retail and hospitality. Although not export industries, they are vital to the UK economy. The retail sector employs nearly 3 million people, approximately 9.6% of the workforce, while the hospitality sector employs 2.4 million, just under 8%. Fewer than 700,000 people work in ‘green’ jobs, if we generously include the 30% in ‘green’ finance, ‘green’ consultancy, or ‘green’ education, and the 18% working in the installation of insulation, efficient appliances, and smart meters.

Despite this devotion to ‘green’ policies, the UK has not stopped using gas; between November 2019, when the fracking moratorium was imposed, and July 2025, the UK has spent £120 billion on gas imports, according to the ONS. (The UK also imported £130 billion in crude oil and £123 billion in refined oil over the same period, in case you are wondering.) But things could be so different if the UK were to develop its gas resources as the US has done.

Fracking and the US economy

The US Henry Hub natural gas price has fallen significantly since the fracking boom in the 2010s, due to the massive increase in domestic supply resulting from shale gas extraction. Before then, US gas was between $6 and $8 per MMBtu now it is about half that amount.

In January 2008, immediately before the fracking boom, the US gas price was $7.68 MMBtu; by March 2012, it had dropped to $2.27 MMBtu, as fracking increased production by 36%. The US Producer Price Index for natural gas declined 56.8% from 2007 to 2012.

Incredibly, before the US shale boom, US Henry Hub prices often traded at a premium to UK gas prices! This has not happened again since 2010. As US production increased and prices fell, UK production was restricted by limiting new well development, preventing fracking, and imposing massive additional taxes on oil and gas companies.

Lower US gas prices not only lowered the cost for US households and manufacturing industries but also fuelled industrial growth. Cheap gas is credited with a 0.7% increase in US GDP by 2015 and the creation of 725,000 jobs by 2014. Cheap gas lowered US electricity prices and encouraged a shift from coal to gas production, which also cuts the associated CO2 emissions in half.

Fracking also helped the US trade deficit: The US went from being a net gas importer, importing gas from Canada and LNG from Qatar, to becoming the world’s largest exporter in 2023, surpassing Qatar and Australia with exports of 91.2 million metric tonnes. This is in stark contrast to 2007, when the US imported 4.6 trillion cubic feet, approximately 88.6 million metric tonnes, assuming a standard methane density.

The UK’s trade has been the reverse of the US’s; the UK was a gas exporter in the early 2000s, but now imports about two-thirds of its gas supply: 45.4 billion cubic metres of gas from Norway, and 128 TWh of LNG from the US (approximately 11-12 billion cubic metres), and 30 TWh of LNG from Qatar. In 2025, the UK is expected to import a total of 28.5 billion cubic metres of LNG, up from 27.5 billion cubic metres in 2024.

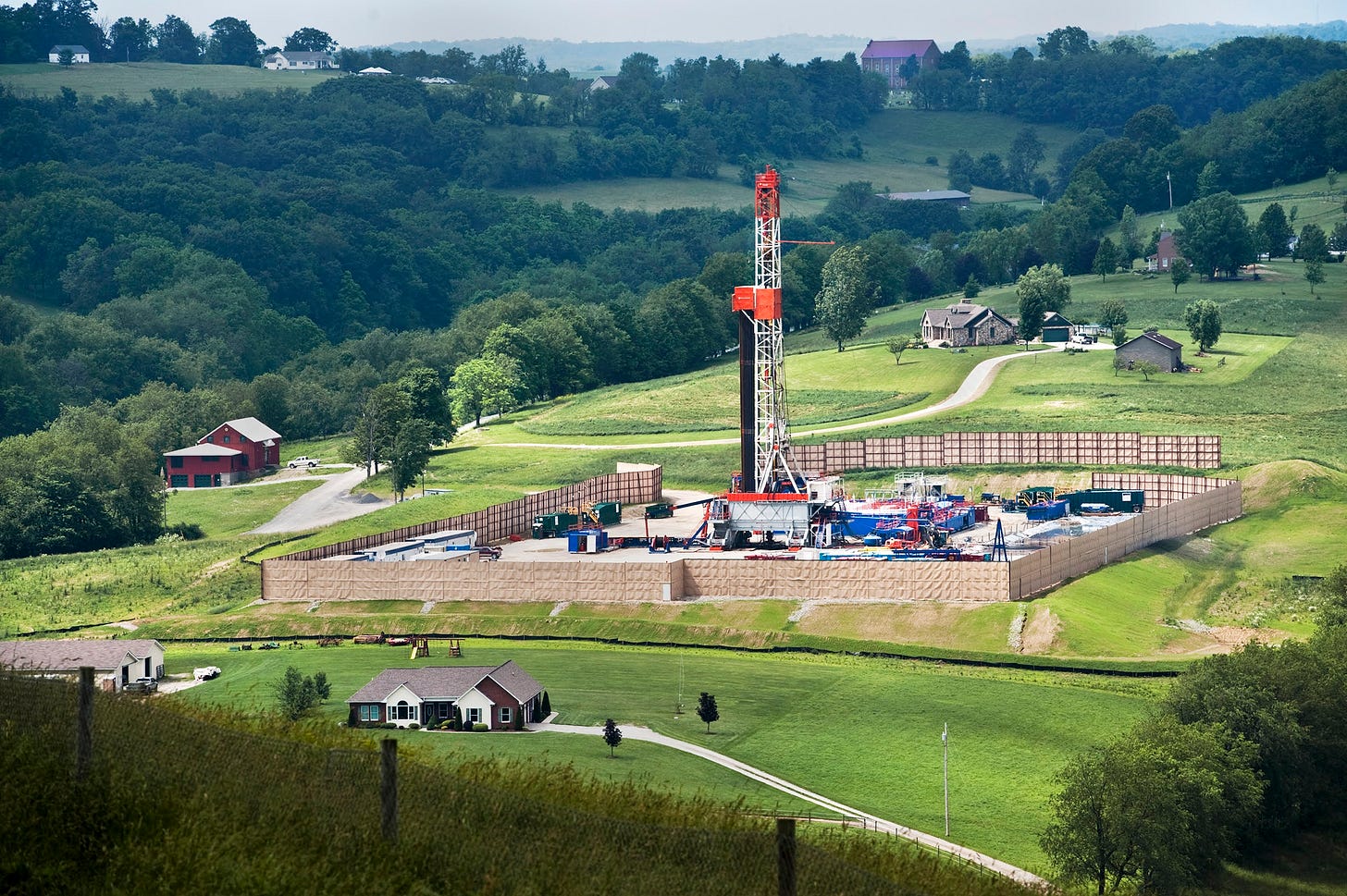

By the way, the photograph illustrating this article is a fracking site in Pennsylvania, USA. Fracking has not turned rural Pennsylvania into an industrial wasteland, as often implied in the UK. But incredibly, in 2022, Michael Gove, then the UK’s Secretary of State for Levelling Up, blocked a planning proposal for a fracking site in South Yorkshire on the rather middle-class grounds that a 3 metre high fence might spoil the view.

There is no global gas price

To add to the absurdity of the UK’s energy price dilemma, Miliband continues to insist that there is a ‘global gas price’ – he has never bothered to look up the natural gas price in other countries to check this. There are many free websites that could inform him, for example, that the US Henry Hub price was only $3.34 per MMBtu on October 3rd. The UK natural gas price is quoted in pence per therm, which converts to about $10.53 per MMBtu – over three times the current US ‘gaseous’ gas price.

Miliband needs to understand that although most natural gas is about 90% methane, there is no global price because gas is expensive and complicated to transport. As a result, the gas price is determined by demand at its location unless a pipeline connects it to other areas. This differs from oil, where prices are similar but vary by grade. Refineries are usually designed to process only one grade of oil. Therefore, the North Sea Brent Crude price is not the same as the West Texas Intermediate or Dubai/Oman Crude prices, although they generally move together.

Converting gas to LNG involves cooling it to -162 degrees Celsius, which also reduces the volume by about 600 times. Cooling the gas is very energy-intensive, consuming approximately 280 kWh to produce one metric tonne of LNG. About 7% to 15% of the gas delivered to an LNG plant is used to power the compressors and refrigeration process. Converting gas to LNG adds about $3.50 per MMBtu to the price, assuming this is done at a large-scale facility on the US Gulf Coast. Shipping the LNG to the UK adds an additional $2 per MMBtu, and regasification at a UK terminal incurs an additional $0.8 per MMBtu. Together, this makes imported LNG from the US comparable to the current price of UK natural gas. This may be why Miliband thinks there is a ‘global price’; however, the UK also imports LNG from Qatar, which is more expensive than UK natural gas and generally about 10% more expensive than US LNG after delivery to the UK.

The UK salvation?

Miliband should be trying to lower the cost of UK gas by removing the excessive taxes and encouraging UK firms to increase supply, not just from the North Sea but also on land and by fracking. Encouraging fracking would bring new entrants into the market, increasing competition and, in turn, increasing supply and lowering the price. While developing the recent natural gas discovery in the Gainsborough field in Lincolnshire could supply the UK with up to 480 billion cubic meters of recoverable gas without fracking, thus avoiding the risk of ‘earthquakes’.

Unfortunately, Miliband’s belief in a mythical global gas price means that he thinks it doesn’t matter if the government puts excessive taxes on UK oil and gas companies. (Yes, this was in an SKY interview; you will find it on YouTube.)

Miliband knows nothing about business. He doesn’t even understand that an oil and gas company’s revenues are determined by the quantity of oil and gas they produce as well as by the price they sell it for, and their profits, which are taxed at 78%, are determined by the revenue minus the cost of producing that oil or gas. When a company’s profits are taxed at 78%, they are unlikely to produce more oil and gas, nor would they invest in expanding their production. They would be better off leaving any reserves in the ground until the UK gets a more sensible government. (Or until Starmer and Reeves have the guts to replace Miliband with someone who understands the importance of Oil and Gas to the UK economy.) Not holding my breath.