The UK faces a significant debt problem, a stagnant economy, and a structural balance of payments deficit. If this isn’t the reason Racheal Reeves was crying in the House of Commons on Wednesday, it should be.

But all of the UK’s economic problems could be solved by the UK playing to its strengths and maximising its natural resources.

The UK is a relatively small island, but it has been blessed with abundant hydrocarbons: coal, oil and gas. But not with uranium, nor with all of the metal ores needed to make wind turbines, nor the critical minerals needed to make solar panels, nor usually the sunshine needed to make solar panels work. Even though this has been an unusually sunny midsummer, during which solar power produced 12.6% of UK electricity, the figure drops to just 6% over the past year: solar power disappears at night and falls to less than a quarter of a gigawatt during the UK’s long, dark winters.

And yet successive UK governments have decided to limit oil and gas exploration and prevent coal mines from being opened even for export, while subsidising wind, solar and nuclear electricity. This is the exact opposite of playing to your strengths. Not only has the UK’s perverse attitude to oil, gas, and coal driven away investment, reduced employment and tax revenues, but it also added £37 billion to the UK’s trade deficit in 2024.

However, all this could change if the UK were to increase its oil and gas production to become self-sufficient again. Offshore Energy UK believes that with a more conducive regulatory and fiscal environment, the UK could double its present oil production, add £200 billion to the economy, support jobs and drive investment into the UK’s energy supply chain.

Alternatively, the UK could just export its coal to Germany, a country that, despite its ‘Green’ veneer, has returned to burning lignite to produce electricity. Both Ed Miliband and Rachel Reeves would win if the UK exported hard coal to Germany – we would lower the world's noxious gas emissions (slightly) and reduce the UK’s trade deficit. Lignite, also known as brown coal, has about half the energy density of hard coal and releases approximately 20% more CO2 emissions per kilowatt-hour, as well as releasing more sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. So why isn’t Miliband encouraging this?

We have been here before

Almost 50 years ago, the UK turned to the IMF for the largest loan ever requested from the IMF, amounting to £3.9 billion. The Loan was needed because Sterling was under pressure due to soaring government debt, equivalent to 50% of GDP, and a current account deficit of £1.02 billion, approximately 0.7% of GDP. (Current account deficit includes trade in goods and services, investment income and transfers.)

These seem like tiny amounts compared to today's economy, with debt equal to 96.4% of UK GDP and a current account deficit of 2.7% of GDP in 2024. However, in 1976, global capital mobility was limited, especially for countries like the UK, which had rising debts and a falling currency. The pound had fallen sharply, losing a third of its value against the US dollar from $2.40 at the start of 1975 to $1.60 by October 1976, despite strict exchange controls for exporters, importers, and investors attempting to repatriate their UK earnings. The Bank of England lost £5.5 billion in 1976 trying to defend the pound, which was roughly 8% of the money supply. UK gilt yields ranged from 14% to 16%. An IMF loan was considerably cheaper, with interest rates linked to IMF Special Drawing Rights around 5%, but it also required public spending cuts and tighter monetary and fiscal policies.

The Labour government did implement the IMF’s required spending cuts, which stabilised the economy. Only half the IMF loan was ever drawn down, and this was repaid in May 1979, just before the general election. The incoming Thatcher government abolished the exchange controls, which revitalised the City of London and attracted international capital. This also freed up a quarter of the Bank of England’s staff who had been employed to manage the exchange controls.

North Sea oil to the rescue

But none of this would have been possible without North Sea Oil. Production in the North Sea began in 1975 with oil from the Argyle field, developed by a small American independent, followed by BP, which started extracting oil from the Forties field. BP was soon joined by Shell and Esso – now known as ExxonMobil.

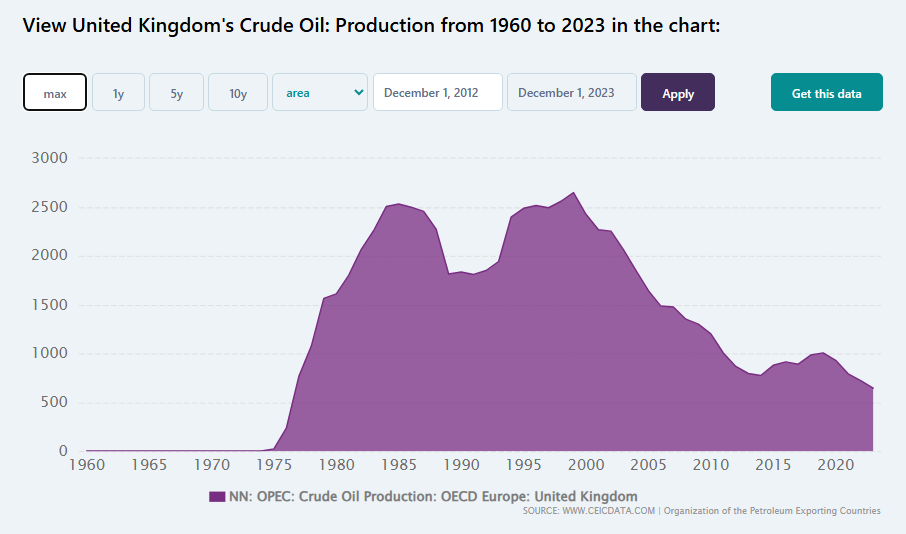

It might be considered sacrilege to mention this during the centenary year of Margaret Thatcher’s birth, but a significant part of her legacy is linked to North Sea Oil production, which rose from nearly nothing in 1975 to 127 million tonnes of crude oil in 1985. This not only supplied the UK with abundant oil for its refineries and feedstock for its petrochemical, pharmaceutical, and plastics industries, but also reduced the UK’s crude oil imports from 112 million tonnes in 1974 to only 35 million in 1985. Meanwhile, the UK’s oil exports increased from one million tonnes in 1974 to 83 million in 1985. The UK had become a net oil exporter, and Aberdeen emerged as the oil capital of Europe.

North Sea Gas

Before 1977, UK gas was known as Town Gas, produced by heating coal or oil to generate gas. This method was both inefficient and hazardous. Town Gas has a lower energy density than Natural Gas, at only 17 MJ per cubic metre, whereas Natural Gas ranges from 33 MJ to 80 MJ per cubic metre. Additionally, Town Gas was highly toxic because it contained carbon monoxide.

Fortunately for the UK, natural gas was discovered off the coast of East Anglia in the southern North Sea in 1965 by British Petroleum at the West Sole Field. This prompted the Gas Council and later the British Gas Corporation to start converting 13 million homes and 40 million appliances from Town Gas to natural gas, a process that lasted ten years, from 1967 to 1977.

Although Thatcher cannot claim credit for discovering North Sea oil and gas, her 1986 Gas Act and the 1989 Electricity Act dismantled the state monopolies and introduced market competition. This encouraged electricity companies to build new, more efficient combined-cycle gas turbine power stations. Simultaneously, the removal of currency controls promoted foreign investment and led international oil and gas majors to invest in the North Sea.

That sinking feeling, again

But now the oil majors are selling up and leaving. Chevron has announced that it will close its Aberdeen office in December 2025, following its earlier announcement last year that it would sell its remaining UK North Sea oil and gas assets after 55 years. Instead, Chevron will focus its business on more profitable regions such as the US Permian Basin, Guyana, and Australia. ExxonMobil is also closing its Aberdeen operations, while Shell is forming a joint venture with Equinor for its North Sea assets. BP has scaled back its UK North Sea exploration but retains stakes in several fields, while TotalEnergies and Repsol have sold off some of their holdings.

This week, one of the UK’s last remaining large-scale oil refineries, PRAX in North Lincolnshire, went into administration. This follows INEOS closing its large-scale oil refinery at Grangemouth in April this year. And while the UK’s junior energy minister, Michael Shanks, claims to be deeply concerned, Sharon Graham, General Secretary of Unite, highlighted the real issue, calling for the government to ‘protect workers AND FUEL SUPPLIES’.

However, we shouldn’t be surprised that oil and gas companies perceive the UK’s attitude towards them as political, punitive, and unpredictable.

The UK’s headline tax rate for oil and gas is now 78%, and it will stay at that level until 2030. The Labour government backdated the Windfall Tax (Energy Profits Levy) to 1 November 2024; they also retroactively applied the removal of the 29% investment allowance to January 2022, so companies cannot claim relief retrospectively. They lowered the decarbonisation allowance from 80% to 66% and extended the Energy Profits Levy from 2028 to 2030. If you thought the five-year ‘windfall tax’ of 75% under the previous Conservative government was excessive, it is now a seven-year ‘windfall tax’ of 78%. However, there will be no relief in 2030 for the beleaguered oil and gas companies; the Labour government is already consulting on how to replace the Energy Profits Levy after 2030.

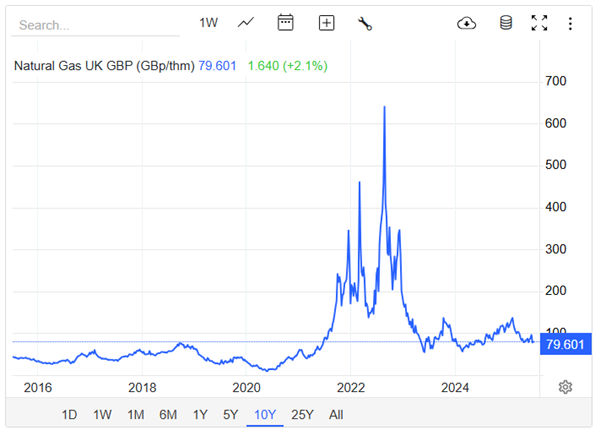

In fairness, the Labour government has maintained the Conservatives’ full expensing for capital investments, which allows companies to deduct the entire cost of qualifying capital assets from their taxable profits in the year the expenditure is incurred. Provided the capital assets are new, not second-hand, purchased, not leased, and the company pays tax in the UK. The Labour government has also retained the Energy Security Investment Mechanism, which will suspend the Energy Profit Levy if the oil price falls below $71.40 per barrel and the gas price falls below £0.54 per therm, provided both prices remain below these thresholds for two consecutive quarters.

The Energy Profits Levy is one of the UK’s most stupid taxes. In 2024, it raised just 0.3% of UK tax receipts and it has helped to drive a profitable industry out of the UK, lowering future tax receipts, employment and increasing the trade deficit as the UK must now import more oil and gas.

There is no longer a ‘windfall’ to justify this tax rate; as you can see in the two graphs above, both the oil price and the gas price are back to their 2019 levels. And even if there were, the best cure for high prices is high prices: they encourage increased supply and discourage consumption, both of which help to bring down prices. Taxing producers when prices are high merely discourages increased supply, thereby keeping prices higher for a longer.

But it is not just the stupid taxes that are driving companies away; the Labour government has also banned the issuance of new oil and gas exploration licences. The Government is also not defending legal challenges to previously approved projects such as the Rosebank and Jackdaw sites, after the UK Supreme Court ruling that Horse Hill Developments’ approval to expand its onshore oil site was unlawful because it did not include a Scope 3 emissions assessment. Scope 3 emissions are not produced by the oil companies but by their customers and by their suppliers. These are not only beyond the control of oil companies, but they may also be outside the geographic area of the UK and would not be included in UK climate reporting; however, they do apparently count in UK planning law. Now, both the Jackdaw and Rosebank developments must resubmit their applications, including Scope 3 emissions assessments.

The Rosebank field was discovered in 2004, and it took nearly two decades to receive government approval. Following extensive evaluations and delays, the UK government granted development consent in 2023. The Jackdaw field was discovered in 2005 and received government approval in 2022. However, this approval process also faced delays due to environmental concerns and regulatory reviews. Environmental groups, such as Greenpeace and Uplift, have played a pivotal role in challenging these approvals.

But reducing Scope 3 emissions from UK oil and Gas production will have no effect on global emissions. China’s, India’s, and other Asian nations’ emissions continue to increase, and if they are not burning UK gas and oil, they will likely be burning someone else's, and producing exactly the same emissions. While blocking new developments in the North Sea when many of the UK's fields have reached maturity changes nothing. The UK still relies on gas for about 40% of its electricity, the majority of domestic heating and for making fertilisers and cement. The UK also relies on oil for transport, farming, bitumen, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and plastics. Even the UK’s Climate Change Committee believes that in a Net-Zero scenario, the UK will still use oil and gas for aviation fuels, petrochemical feedstocks, backup electricity generation, grid balancing and industrial process heat.

All that the UK’s high taxes and production blockages are doing is increasing the country’s trade deficit.

Two sides of the same sea

But this oil and gas exodus isn’t happening on the Norwegian side of the North Sea. The Norwegian industry is booming. Oil and gas companies are expected to make a record investment of NOK 275 billion (about $25 billion), and output is forecast to increase to 4.2 million barrels of oil equivalent a day, driven by seven new fields, four brownfield expansions, and 45 exploration wells.

So, although oil and gas companies in both Norway and the UK face a total marginal tax rate of 78%, and new oil and gas developments in Norway must also assess Scope 3 emissions as part of their Environmental Impact Assessments, oil and gas companies are not leaving Norway primarily because Norway’s attitude to oil and gas production is the opposite of the UK’s.

Norway recognises the important contribution oil and gas make to its economy and has created a predictable environment for investment. They reward investment with upfront deductions and refunds. They have invested in the electrification of offshore platforms to lower upstream carbon emissions. The Norwegian government owns 67% of Equinor, which operates internationally, including in the UK, as well as being the largest operator on the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Unsurprisingly, unlike the UK, Norway has maintained a substantial fuel trade surplus since 1989. Fuels make up two-thirds of Norwegian exports, and the United Kingdom is its largest export market, buying a quarter of Norway’s fuel exports.

What can the UK learn from Norway?

Norway has fast-track approvals for new fields. It allows new fields to be connected to the existing network of pipelines and platforms, and the government actively invests in offshore energy, with petroleum accounting for one-fifth of all capital investment in the country. Companies can deduct 100% of the investment costs upfront, including exploration, research and development, financing, operations and decommissioning. Companies can consolidate revenue, investment and losses between fields. Companies with no taxable income can receive cash refunds for losses, helping new and small operators to get started. And most importantly, Norway continues to issue new licences and encourage drilling, with 42 exploration wells completed in 2024, resulting in 16 new discoveries.

The North Sea to the rescue

The UK can’t survive without imported oil and gas. Yet still, the UK is preventing new North Sea fields from operating with excessive taxation, regulation, and litigation. The UK has gone from being self-sufficient in natural gas to importing 33 million tonnes in 2024, two-thirds of which came from Norway. The balance is imported as LNG from the US, Qatar, Trinidad and Tobago, Algeria, Peru and Angola.

The UK owns all of the western side of the North Sea, stretching from north of the Orkneys down to the Channel. In contrast, the other side is divided between Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. But still the UK doesn’t extract enough oil and gas to meet its domestic needs.

But now we have an additional problem. The machinery needed to collect solar and wind and convert them into electricity is not built in the UK. Just as the EU has found itself reliant on Russia for gas, the UK is now dependent on China for wind turbines and solar panels. Importing this equipment adds to the UK’s trade deficit.

China was even meant to provide the financing to build the UK’s newest nuclear plant, Hinkley Point C, before it withdrew from the project in 2023. The project's costs have ballooned from £18 billion to £46 billion, and the start date has been pushed back from 2025 to 2029. Now a private capital group, Apollo, will provide £4.5 billion in debt financing as unsecured debt at an interest rate of almost 7%. The Government has also pledged an additional £11.5 billion of state funding to the Sizewell C nuclear plant. And a further £2.5 billion towards the development of 3 Small nuclear reactors. These won’t come online before 2030 at the earliest.

The Chancellor needs to dry her tears and explain to Ed Miliband, who initiated the UK’s industrial decline in 2008 by passing the Climate Change Act and establishing the Climate Change Committee, that the UK cannot sustain its enormous trade deficit, nor can it afford to lose more industries, including the oil and gas sector. The Labour government should be doing everything possible to safeguard industrial jobs, rather than contributing to their loss. The UK needs to capitalise on its strengths—exploiting its oil, gas, and coal reserves—and join countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, and Norway to become a net exporter of fuels, or at least a smaller importer.

Although nuclear power might eventually save what remains of the UK's industry by 2030, a quicker alternative is to increase North Sea oil and gas production and coal exports. All this requires is a change in attitude from the UK government.

The UK has to be more Norway.