Britain has been on a roller coaster of government announcements over the last few weeks, with one announcement quickly negated by another.

Two weeks ago, the government announced a Free Trade Agreement with India and an Economic Prosperity Deal with the US. Things were looking up for Britain. From an agri-food perspective, the US deal included cheaper imports of US ethanol, now a requirement in UK petrol, as well as a reciprocal quota for 13,000 tonnes of beef, provided the beef meets the importing country’s food standards, and with the promise to continue to negotiate lower tariffs on cereals, fruit, vegetables, animal feed, tobacco, soft drinks and shellfish. The India FTA appears to have excluded agrifoods such as sugar, milled rice, pork, chicken and eggs, but the UK’s whiskey and gin manufacturers, also counted as agri-food exports, will benefit.

But this week, the Government shattered the illusion that the UK was an independent trading nation with its EU ‘Reset’ announcement. To compare this Reset to swapping a cow for a handful of beans would be generous. There is no chance the beans even lead to a magic kingdom in the sky, but they may well be magic disappearing beans: the promised use of EU passport e-gates has already disappeared – apparently, it is outside the EU’s competency.

There is nothing good about the Reset or Capitulation Agreement. I will stick to the trade and agricultural issues now, but in brief: the defence agreement will cost more than it's worth: the fishing community sell-out is abhorrent and unnecessary as shall become apparent at the end of this article: and the ‘youth’ (up to 35 plus dependants) mobility plans will put more downward pressure on UK wages and more upward pressure on the price and availability of accommodation in London. While joining the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme and its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is so bad that it will require another essay.

EU SPS dynamic alignment

The Capitulation agreement includes the introduction of a ‘Common Sanitary and Phytosanitary Area’ covering the EU and the UK. Although Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) rules only refer to a country’s regulations on human, animal and plant health, reading the EU’s statement on the reset, rather than the UK government’s PR publication, it is apparent that this Common SPS Area doesn’t just cover SPS regulations. It also covers food safety, consumer protection rules for the production, distribution and consumption of agricultural products, as well as the regulation of live animals and pesticides, the rules about organic products, as well as food and agricultural marketing standards.

In other words, this SPS Area gives the EU the right to determine all aspects of food production in the UK and all UK food imports. And to add insult to injury, the UK will have to pay the EU for the indignation of being forced to follow EU regulations.

At present, all imported foods must meet the UK’s SPS regulations. Under the capitulation agreement, goods imported into the UK will need to meet the EU’s SPS regulations instead. And this agreement requires immediate dynamic alignment, so if a shipment of apples is on route from South Africa to the UK, but the EU changes its Maximum Residue Level for pesticides (again) while the apples are on route, then the apples won’t be able to be sold in the UK. This would cost importers and their freight insurance companies a fortune. This could cost so much that importers stop importing goods from non-EU countries and exclusively buy from EU producers to avoid these risks. Could this be the EU’s motivation? Undoubtedly. So, UK supermarket shelves in spring and summer will be full of French or Spanish apples that have been kept in cold storage for six months, rather than fresh apples from South Africa, Chile or New Zealand.

Why would any country do this?

The government claims that its capitulation to EU food suppliers will save UK supermarkets money and make it easier for UK producers to export to the EU. But there are gaping holes in both feeble excuses:

First, why should all UK farmers adopt the EU’s unscientific SPS rules, the subject of regular complaints at the WTO, when most of them don’t export food to the EU. The UK is a major food importer from the EU, not an exporter. EU farmers and consequently EU food producers are still subsidised by the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) payments. Unsubsidised UK goods are too expensive to compete in the subsidised EU market.

Second, the UK has never made importing goods from the EU onerous, as it needs the food. SPS alignment will only benefit a handful of supermarkets by slightly reducing their import costs and increasing their profits.

But with the political nous of a gnat, the UK Prime Minister even tried to promote EU subservience from a Lidl store in North London. Lidl is a privately owned German Supermarket chain, part of the German multinational Schwarz Group. Schwarz Group can definitely afford to pay their own trading costs; no need for UK taxpayers to help out.

EU farm subsidies will still be a major trade barrier.

Even when the UK was a member of the EU, EU agri-food products were cheaper than UK goods because the EU has more farmland, lower farm wages and lax animal welfare. But at the time, both UK and EU farmers received CAP payments. Now, UK CAP payments have been discontinued and replaced with non-farming payments for Environmental Land Management or for installing solar panels on farmland rather than farming. These payments will help with farmers' bills, but they don’t lower food prices; if anything, they reduce supply and increase prices. Subsequently, increased UK prices make the UK market even more attractive to subsidised EU farmers and food manufacturers.

In general, UK and EU farmers are direct competitors, producing the same products at the same time. Agricultural subsidies are an unambiguous trade barrier: they make UK products uncompetitive in the EU and allow EU CAP-subsidised imported goods to undercut UK products in the UK’s domestic market. Rather than transferring the UK’s standard-setting to the EU, the UK should add retaliatory tariffs to imported EU goods to counterbalance EU subsidies.

The EU are the last people to put in charge of UK food standards

But letting the EU control UK food standards must be some sort of mistake. Perhaps the AI LLM confused who should be monitoring whom. After Brexit, food imported from the EU is checked at UK ports in the same manner as food imported from elsewhere. Since September 2022, UK customs agents have seized 600 consignments of diseased meat coming from the EU, with another 60 tonnes seized in the first quarter of 2025. Under the EU’s new SPS Area, such health checks will apparently no longer be conducted, so we should expect to find many more diseased products on UK supermarket shelves.

However, it is unlikely there will be any reduction of border checks for products going in the other direction. The EU is not troubled by Eastern European pork with African swine fever, but it is driven crazy by the idea that any food may have bypassed the EU’s tariff system. The EU will be checking for any transshipments of goods imported into the UK under the UK’s new trade agreements with Australia, New Zealand, the CPTPP, India, or the US. So, I expect the French customs authorities to continue to stop vehicles entering the EU to ensure there is no Texan beef, or Peruvian vegetables or Malaysian palm oil in the consignment.

The EU is also the last people to be put in charge of animal health and welfare

Rather incredibly, the UK is also handing over control of its animal health regulations to the EU. There are currently three countries in the EU with Foot and Mouth Disease outbreaks (Germany, Hungary and Slovakia), and more than 1,000 separate [African swine fever] outbreaks registered in the EU last year. But regardless of this appalling record, the EU will be determining the UK’s animal health regulations. Is this a joke?

As for EU animal welfare, where to start? Four countries and one state (France, Hungary, Bulgaria, Spain, and Wallonia) still allow the force-feeding of geese with a tube stuck down their throats until their livers swell to 10 times their normal size. The UK banned this practice almost twenty years ago. The UK has also banned live animal exports of cattle, sheep and pigs for slaughter abroad, i.e. slaughter in the EU. Why don’t we trust them? The UK literally has charities raising money to help mistreated donkeys in Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. Are these really the right people to be determining UK animal welfare regulations?

Plant health and yields will also deteriorate.

EU rules have stopped EU farmers using more efficient science-based agricultural processes. Internationally, the use of GM crops has lowered the use of fungicides, insecticides, and herbicides, but the EU is not interested in this evidence; it prefers the unscientific precautionary principle. Illogically, the EU has only banned the cultivation of GM crops by EU farmers; it still allows its farmers to import GM soy from Brazil to feed EU chickens and pigs. The EU has also banned its farmers from using neonicotinoids on rapeseed and sugar beets, but when this caused yields to collapse, EU users imported rapeseed from Ukraine instead, even though Ukrainian farmers still use neonicotinoids.

The EU has also made getting permission to use gene-edited plants and animals extremely difficult and time-consuming, so the new organism will have been superseded by the time the permission is granted.

Since leaving the EU, Ag-tech research and development has once again become an important industry in the UK. Scientists at the Roslin Institute in Edinburgh have successfully used gene editing to create pigs that are resistant to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome. UK scientists have developed disease-resistant potatoes, bananas and sugar beets, but all this could be abandoned when the EU takes charge of UK agricultural regulation.

Worthless exceptions and ECJ control

To make this ludicrous capitulation even worse, the EU has generously allowed the UK to have the same ability to protect its own biosecurity, just as if it were an ‘EU member.’ But EU members don’t have the ability to change anything – EU members must simply do what Brussels tell them.

The EU has generously said it would allow the UK to have a ‘short list’ of limited exceptions to dynamic alignment provided the exceptions: (i) do not lead to standards lower than the EU’s, (ii) do not allow competition in the UK market for EU goods and (iii) and are not exported to the EU. This would also allow the EU to stop any UK agrifood goods export that may contain non-EU compliant imported ingredients.

But never fear, if we don’t like the EU’s decisions, we can go to arbitration at the EU’s ‘Court of Justice’… It is incredible to think that the PM thought this would justify his capitulation. The UK’s inability to ever get a positive outcome from the ECJ was one of the many reasons why we left the EU.

The EU has also offered the UK ‘access’ to relevant European Union SPS agencies, systems and databases. Access in ‘EU-speak’ does not mean public scrutiny, debate or influence. The EU may allow UK delegates to read a hard copy of the text in a dark basement room with no access to the internet and no permission to copy the documents or reveal the contents to the media. (This actually happened during the EU’s TTIP negotiations.) But they won’t be able to change anything.

Why agree to this when the UK is a large NET IMPORTER of EU agrifood?

Unfortunately, there has been a large amount of misinformation in the UK press about the extent of UK food exports to the EU. There are made-up stories that sausages and shellfish couldn’t be exported to the EU, both of which are untrue. Sausages just had to be frozen, just as much of the meat the UK imports is frozen. While crustacean and mollusc exports just exclude goods processed outside the UK. More on that later.

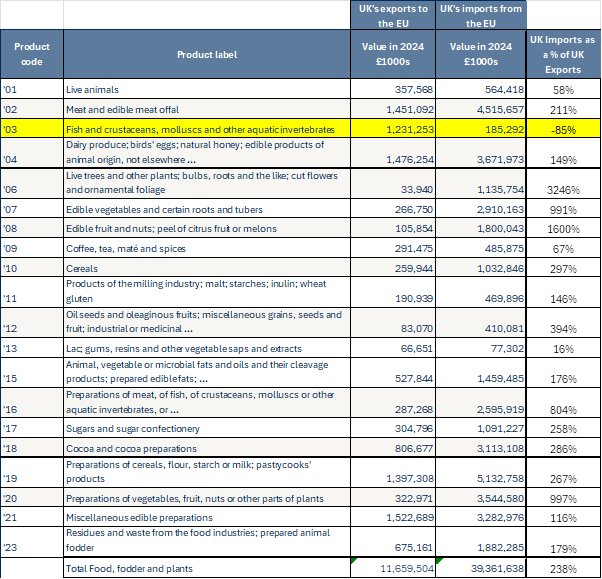

Due to the repetition of this misinformation, even the British Meat Processors Association seems to believe that the UK is a large agricultural exporter to the EU and therefore must comply with EU standards in order to export there. (I’m not making this up, they actually said that.) But the UK is not a large food exporter; it is an importer of EU goods. The UK imports almost four times as much food and live animals from the EU as it exports to it, according to the ONS. If exporters need to produce to the standards of their markets, then it is the EU that should align with the UK’s standards.

Luckily, the Country Land and Business Association has a better understanding of which way the trade flows. Even the National Farmers Union, once a Europhile, could smell a rat, as could the Agricultural Industries Confederation; both were worried about the effect of the UK’s Precision Breeding Act and dynamic alignment with the EU SPS regime. Joining the EU’s SPS Area will simply give the EU’s subsidised agricultural producers unfettered access to the UK market and drive out competition from non-EU producers

So what about the FISH?

From the table below, which uses HMRC data by HS product code rather than ONS data, it is obvious that the EU exports many multiples of all types of food and fodder to the UK than it imports from the UK, with the exception of fish.

This seems strange, as many politicians have claimed that the UK had to give up its fishing waters to the EU for 12 years as part of the capitulation agreement because UK fishermen could not export their goods to the EU. This is patently untrue. The UK exported almost 7 times the value of fish to the EU in 2024 than it imported from it. Fish is the only product sector where the UK exports more to the EU than it imports.

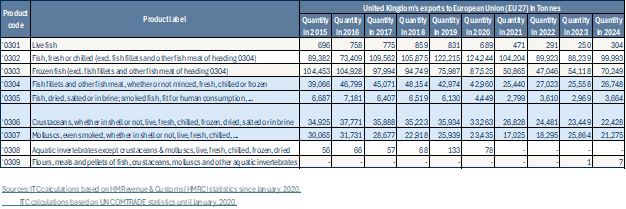

Reviewing the Fish trade data in tonnes, while fresh and frozen fish exports were higher in 2024 than in 2023, the main export reductions are in filleted fish, dried fish, or shelled crustaceans and molluscs. This is due to the Rules of Origin in the UK EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), as fish must be wholly obtained in the UK to be classed as a UK export under the TCA. Export tonnages of filleted fish, dried fish, shelled crustaceans, and shelled molluscs were stable until 2020, then dropped suddenly to a lower but also stable level, as can be seen in the blue-shaded area in the table below. It is likely that the sudden reduction in exports was due to processing outside the UK. Pre-Brexit figures would have included fish, crustaceans or shellfish processed in China or Vietnam, and distributed to the EU via the UK. This trade may still be happening, but it will no longer be counted as a UK export.

Unfortunately, because UK politicians still don’t understand this structural change in the trade data, they have lumbered the whole country with EU SPS control.

Joining the EU’s SPS Area will drive out competition from non-EU producers and drive up prices.

It is somewhat suspicious that just as the very gradual reductions in UK tariffs in its free trade agreements were beginning to get to a level where Australian and New Zealand products are competitive with EU products, the EU has sprung its trap to take back control of UK food markets. In 2024, the UK imported 9,700 tonnes of New Zealand cheese for the first time. This is about a tenth of the cheese the UK imports from Ireland, but it is still a start. The UK also imported 17,800 tonnes of Australian lamb and 5,200 tonnes of beef in 2024. Both are a fraction of the meat the UK imports from Ireland. But these amounts will grow as the quotas are increased each year. Add to this the food that the UK will be able to import from other CPTPP countries this year and the potential for a full US FTA, and it is obvious why the EU wants its captive market back. It was just idiotic of Starmer to give it to them.

Tying the country to EU suppliers with the same seasons and weather as the UK will increase UK prices and make UK food supplies vulnerable to regional disruption. Only competition with multiple suppliers will lower prices for UK consumers and ensure UK food security.